What was it about? What were the goals?

Not to be

confused with Supremacism (meaning racism, basically), this was an art movement

founded by Kasimir Malevich in 1913, focusing on simple geometric shapes,

arranged in compositions of varying complexity and limited colours, emphasizing

dynamic placement of shapes. The goal was to ignore the real world and

everything in it, and break everything we see and know into simple, pure

abstract shapes, and see what kind of feelings and qualities they emote.

Malevich wrote,

“Under Suprematism I understand

the primacy of pure feeling in creative art. To the Suprematist, the visual

phenomena of the objective world are, in themselves, meaningless; the

significant thing is feeling, as such, quite apart from the environment in

which it is called forth.”

It was a

kind of experimentation, and Malevich even went so far as to say there was a

spiritual aspect to his work.

A bit of historical context:

Malevich

began painting around 1900, experimenting in a number of different art styles:

Symbolism, Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, and then Futurism. In 1913, he

began to form his new style while designing the sets and costumes for

Kruchenykh’s Futurist opera, Victory Over

the Sun. This led him to a series of works he displayed in 1915 at the Last

Futurist Exhibition of Paintings ,10 in Petrograd. With a slightly distorted

black square hanging in the corner of the room, like a Russian icon, he

launched the movement.

The Sick Man,

by Vasili Maximov, 1882 (not a Suprematist)

This artwork shows a typical Russian iconic corner. People would pray to these for help.

Last Futurist Exhibition of

Paintings ,10 in Petrograd, 1915.

Malevich wrote a great deal to explain his

ideas. When he first exhibited his 1915 show, he wrote “From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism.” It was a big

success, and Malevich formed a group of like-minded artists. They started a

journal, and Malevich then got a job teaching art in Moscow.

In

1928, Stalin decided he didn’t like abstract art. He confiscated Malevich’s

paintings, and forbade him to continue his Suprematism. Part of this had to do

with Malevich’s anti-political views, writing:

“Art no longer cares to serve the state and religion,

it no longer wishes to illustrate the history of manners, it wants to have

nothing further to do with the object, as such, and believes that it can exist,

in and for itself, without ‘things’. . . ”

Malevich

kept painting, trying to reinvent representational art in his portraits of

everyday peasants and workers. However, he still wrote in protest, The Non-Objective

World: The Manifesto of Suprematism, so

that his works would be understood. In 1930 he visited Poland and Germany,

where the Soviet Union suspected he was spreading his artistic ideas, so they

put him in prison for two months.

Malevich continued to paint realistically for five

more years until he died of cancer (he signed all his works with a small black

square). At his funeral in 1935, his casket, tombstone, and the car that drove him

there were all decorated with a black square.

How was it represented in the other arts –

music, architecture, and literature?

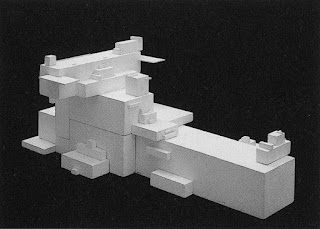

Although

less famous, Malevich began to draw 3D views of his compositions, taking them

in a more architectural direction, and then began building plaster models of

his works. Although they weren’t buildings, per se, they were suggestive of

buildings, and were a huge inspiration for Zaha Hadid, who was one of the

leading, international architects of our time.

Architecton, 1923-8, Malevich

Besides this, Lazar Khidekel managed to become a successful Suprematist

architect in Russia, surviving Stalin, and building the Club for Red Sport Int.

Stadium and a cafe for the Paris World Fair of 1937.

Was it great?

No. Not in

comparison to the greatest artists of other movements. But, that doesn’t mean

it wasn’t successful, attractive, or inspiring. It was all these things, at

least to some extent. Suprematism is basically the culmination of one artist

trying his hand at many different styles of art, and in the end deciding to

start over from scratch – to reinvent art, one shape at a time. It’s easy to

look at his simplest works, and think, “This emperor has no clothes.” But, you

shouldn’t look at these as individual artworks. Back in 1915, they were all

hung together in such a strange, haphazard way that they formed one large art

installation. Think of them as a sequence, like an animation.

Ok, so maybe it’s still not that impressive, but the big simple squares

shouldn’t be thought of as artworks so much as building blocks, almost like

one-celled organisms, from which Malevich’s other artworks evolved. And in

these works, he showed a good sense for design as he created compositions that

were asymmetrical yet balanced, playful, and dynamic. Some are better than

others – that’s how experiments work.

You might be surprised to learn that many artists do this same thing as

an exercise to improve their compositions. Here’s an example of illustrator

William O’Connor drawing thumbnail sketches in the style of Franz Kline (not a Suprematist), to

find the best composition for his work:

Echoes, by William O'Connor

Were Malevich’s works really spiritual? Evocative? Are the feelings you

get from his work any more “pure” than when you see a Rembrandt, Klimt, or

Michelangelo? I would say no, that was just his arrogance getting the best of

him. But, I still see value in his art. Malevich was on to something, and it’s

a tragedy that Stalin prevented him from continuing his work, right when it was

developing into something close to great. In the end, Malevich’s black square

became impressive, not as art, but as a sign of protest against Stalin’s

tyranny.

Wait a minute. Didn’t Kandinsky do all this

before Malevich?

Nope. It’s

true that Kandinsky was older, and went into pure abstraction around 1911, and

both he and Malevich were showing abstract art in the Der Blaue Reiter group. But

Kandinsky’s improvisations were more globular, brightly coloured, Fauvist, and

messy. He didn’t mimic Malevich’s geometric work till the 1920’s. Both artists

used abstraction to explore ideas of spirituality and inner feelings, so they

had a lot in common, but both were distinct.

Wait another minute, did Malevich just do this

because he couldn’t draw or paint realistically?

No, he was

a decent painter both before and after Suprematism – not the best, but decent,

for the times:

Some

leading figures:

Wassily

Kandinsky (1866-1944)

Kasimir

Malevich (1879-1935)

Aleksandra Ekster (1882-1949)

Lyubov Popova (1889-1924)

El Lissitzky

(1890-1941)

Sergei Senkin (1894–1963)

Ilya Chashnik (1902-1929)

Lazar Khidekel (1904-1986)

A look at how Malevich's ideas evolved:

Black Square

Black Circle

Four Squares

Painterly Realism - Boy with a Knapsack

Black Rectangle, Blue Triangle

Rectangle and Circle

Eight Red Rectangles

Airplane Flying

Suprematist Composition

Supremus No. 50

Suprematist Composition

Suprematist Composition

Suprematist Composition

Supremus No. 58

No comments:

Post a Comment